The story of a kind man I never met and the catfish for which he became famous

By Ari Weinzweig

Uncle Joe Burrough’s Whole Fried Catfish used to be a regular dish on the Roadhouse menu, and now pops up as a seasonal special. I’m glad we keep bringing it back—I tried some the other day for the first time in a long while and was reminded just how tasty it truly is. Moist, meaty, delicate, with the crunch of the super flavorful Anson Mills artisan cornmeal on the outside, and a sprinkling of garlic salt that adds a bit of culinary embroidery to an already excellent dish. It’s served up alongside the Anson Mills grits (made with a different corn and a different milling texture than the cornmeal), long-cooked collard greens, and a ramekin of mustard coleslaw. Having this classic fried catfish for dinner would be the making of a great night!

In “A Taste of Zingerman’s Food Philosophy,” I encourage all of us (myself included) to “Get curious about the story behind your food.” Without knowing the story, I always say, the food may be fine—but we’re missing so much of the background that makes it what it is. In the same way that knowing a person only by their job title or as an offshoot of their family tree does them a disservice, it is true for food. We need to know the story to truly know, appreciate, and understand what we’re eating.

About Joe Burroughs

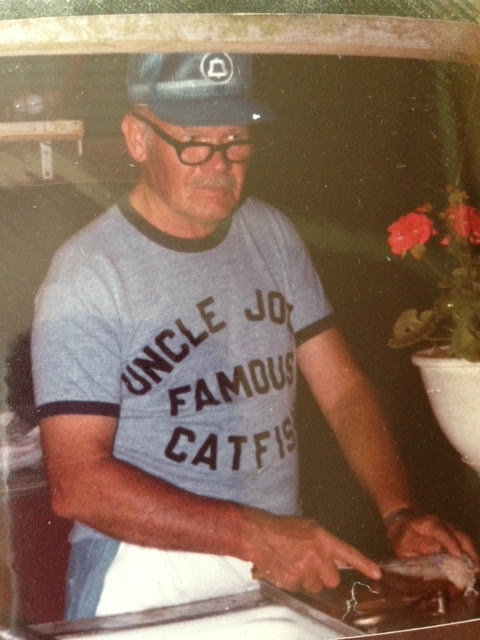

The story of the Roadhouse fried catfish begins with a guy named Joe Burroughs. In his community of Albertville, Alabama, he was known to most folks as “Uncle Joe.” I never met Joe Burroughs, but he was the father of my long-time friend Peggy Burroughs Markel, who for many years has co-led the Zingerman’s Food Tour to Tuscany. I know Joe Burroughs’ beautiful story only through her. American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, who spent much of the 20th century recording little-known traditional music to preserve it for posterity, believed that “traditional songs are the poetry of everyday people.” In a culinary context, dishes like this catfish offer the same loveliness for cooking. They are culinary poetry from the back kitchens of the country. Every time we serve the catfish, I come back to the story of Joe Burroughs.

After Uncle Joe passed away in 2008, Peggy shared this story with me. He went to school at Auburn, then went into the army in WWII, where he spent most of his time in Italy and North Africa. Not surprisingly, the story her father told about the world was influenced greatly by what he experienced there.

He expressed how the Italian people reminded him of his own people, who grew gardens and loved to cook, even though times were rough. He was inspired to write poetry and sculpt in alabaster. … His heart was broken open by the beauty of Italy. He was happy to return home, but the memories of Italy were constantly on his mind, in his expressions and countless tales told over and over again.

Joe went to work for South Central Bell. He was a telephone man, a supervisor, who taught other men how to be fearless on cold stormy nights high up on a telephone pole. His ‘men’ loved him, just as they did when he was 1st Sergeant in Communications. In his private life, he was a gentleman farmer and caring family man. He was creative and artistic. He expressed himself best as a gardener and cook. He took over for my mother on the weekends and it was always a party. Fried catfish on Friday night, steaks on Saturday, and omelets on Sunday night. My mother made Sunday lunch—fried chicken. He loved growing and pickling peppers and was known as a master pepper pickler.

He had a passion for frying catfish. The Tennessee River was a stone’s throw away and he was down to visit his good friend, who we called Uncle Charlie, often. Uncle Charlie had a boathouse on Pole Cat Hollow, an offshoot of Guntersville Lake, where the TVA created 800 miles of shoreline around the foothills of the Appalachian. We grew up swimming in the river, boating, waterskiing, and chowing down on catfish, hushpuppies, and home brew. After all, we lived in a dry county. My dad liked his beer and we had to drive to the next town to get it. We had two refrigerators out back by the Bar B Q pit. One was for beer and the other was a smoker. If you got it mixed up, you’d open the fridge door and find catfish hanging upside down by their tails.

The Tennessee River was a goldmine for catfish—catfish farms were not even invented yet. I can still remember how proud I was as a kid to learn how to take my fork and go up the spine of a freshly fried fish, still steaming, filet it and dab it into some homemade “goush”; an equal mix of catsup and mayonnaise. It was so good. My sisters and I would turn on Elvis Presley and “do the mashed potato.” Wasn’t a Friday night that I didn’t go out on a date smelling like fried fish. At that point, Mama made him start cooking it outside of the house. There he built his domain. … His cast iron deep fryer, full of Mazola, kept the fires burning until everyone had their share. The bone plates were stacked high. All of our friends came willingly. It was the place to be for the best food in town. “Uncle Joe’s famous catfish” right in our own backyard. He was inspired and designed a room off the house and thought to start a small café complete with a conveyor belt, designed to take the fried fish to people sitting around the bar. He was ahead of his time.

Uncle Joe Burroughs died peacefully and quietly in his sleep in the second week of July 2008. Peggy shared this: “The lesson for me? Kindness and gentleness is the key to happiness and a peaceful passing.” Joe never built the café he dreamed of, but in the spirit of Alan Lomax’s work to record people who might never have otherwise been heard of, I really wanted to have his catfish on the menu.

The catfish dish on the Roadhouse menu is a tribute to the memory of the kindness and gentleness and generosity with which he moved through the world. Sharing his story here is another of my “secular prayers,” a hope that we can live lives based around generosity, beauty, and coming caringly together around good food the way Uncle Joe did for so many years. When you raise your forkful of delicately fried catfish at dinner, consider giving a quiet “toast” to Uncle Joe, and the joy he brought to the world. And if you want to channel Peggy’s childhood and bring this touching fish story alive, we can happily bring you the ketchup and mayonnaise to make a bit of Burroughs’ family “goush” to go with it.